Phyllis Webstad Shares the Change That’s Possible With a Powerful Story

Phyllis Webstad—Indigenous author, activist, and founder of Orange Shirt Day—shares the change that’s possible with a powerful story

At age 6, like most Indigenous Canadians of her generation (and several others), Phyllis Webstad left her home—she lived with her grandmother in the Secwepemc Nation—to enroll in the Residential School System, which essentially reeducated Indigenous children to assimilate into mainstream society and learn to devalue their cultures.

Webstad’s grandmother brought her to town shortly before the school year to buy her new clothing, and Webstad—who gave the closing keynote at AFP ICON 2024 in Toronto—picked out a bright orange shirt with a collar and three buttonholes, into which a shoelace of sorts could be threaded. “It was the early ’70s—the psychedelic, bright era,” she says. “That’s the memory I have of being so excited to finally be going to school. Like, ‘I’m a big girl!’”

But as Webstad’s grandmother sadly already knew, the excitement of wearing that orange shirt would be short-lived. When Webstad first arrived at St. Joseph’s Mission Indian Residential School near Williams Lake, British Columbia—which by 1973 was more of a boarding house than an actual school, as children slept and ate there but were bused to attend public school—one of the first steps taken to “mainstream” the Indigenous children was to confiscate their clothing, and replace it with drab, nearly identical, likely bulk-purchased communal clothing.

“I don’t have a memory of wearing my clothing again,” she says. “It was probably a good sale. They didn’t give a [hoot] what we looked like. We were at a lineup, like prisoners with their arms out. And whatever we got, we got. If it was too big, too bad. If it was too small, too bad.”

Webstad spent one year at St. Joseph’s Mission, and during that time she experienced the psychological trauma of disassociation. “It really affected me—who I was, how I thought about myself, and how I treated myself, even up until today,” she says. But it didn’t entirely define her: “I had a life before residential schools, and residential school was a one-year experience, and I had a life afterward,” Webstad says.

Once Webstad reached adulthood, she earned diplomas in business administration from the Nicola Valley Institute of Technology and in accounting from Thompson Rivers University. But her early life experience with the Residential School System, along with that of four generations of her family, guided her toward telling her story through both speaking and writing. And the confiscation of her orange shirt proved to be a potent symbol of the wrongs of the Canadian Residential School System.

Inflection Point

An inflection point came in the early 2010s, when Canada’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) toured the country to hear the truths of survivors, a process that culminated in a final report published in 2015, now housed at the National Center for Truth and Reconciliation, based at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg. When the TRC tour reached Williams Lake in 2013, Webstad appeared as a survivor representative and told her story. “We wanted Indigenous people, obviously, but non-Indigenous as well, to know that they were invited to come and hear the truths of survivors,” she says. “So, we had two media events.”

In order for the world to be different, people need to know our truths, and truth comes before reconciliation. That’s usually my approach.

—Phyllis Webstad

Inspired by Webstad, a woman in attendance printed up cards and created a Facebook page advertising “Orange Shirt Day,” and the concept instantly went viral. “I didn’t just get out of bed one day and decide that September 30 would be Orange Shirt Day,” Webstad says. “There’s a whole list of people and events that happened for me to be able to tell my story.” In addition to Orange Shirt Day, September 30 is now the National Day for Truth and Reconciliation, although she says that “did not replace Orange Shirt Day. It is and will always be Orange Shirt Day, first.”

Webstad and those with whom she consulted chose September as the month for Orange Shirt Day because it was the time of year that children were taken from their homes and families. They chose the last day of the month to give teachers and students time to settle in and to have time to plan communitywide events commemorating the day. The day was also created in response to the TRC commissioner, who issued “a challenge to Canadians to keep the conversation going after the TRC wrapped up” in 2015, she says.

During the TRC event, Webstad had also overheard an elder say that September was “crying month,” and that helped underscore the timing. “I knew then that we had chosen the right day and month for Orange Shirt Day,” she says. “She said it was ‘crying month’ because we, at the so-called schools, were crying for our homes and our families, and our families and our homes were crying for us.”

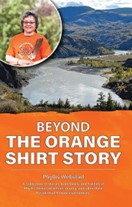

Webstad since then has published six books that share her story, including The Orange Shirt Story, Phyllis’ Orange Shirt, and Beyond the Orange Shirt Story. In 2015, the Orange Shirt Society was incorporated, which survived as an all-volunteer effort with no physical structure until 2019, when the group raised enough funds for it to become Webstad’s full-time occupation and to open an office in downtown Williams Lake. The society is now housed on Indigenous lands in Williams Lake, three minutes from the site of St. Joseph’s Mission.

“The building is no longer there,” Webstad says. “But it’s where three generations of my family attended residential school.” (Webstad’s son would attend the last residential school in Canada, St. Michael’s in Saskatchewan, which closed in 1996.) Beyond the Orange Shirt Story tells the story of all six generations with whom she has been acquainted, starting with her great-grandmother on down to her two grandsons. “There is a curriculum for my books in the schools, and they’re also [translated into] French,” she says.

Webstad finds hope in the fact that her grandchildren are the first in five generations to be raised entirely by their parents. “Granny, mom, me, and my son weren’t,” she says. She’s also concerned that because the residential schools are now a part of history, that could lead their horrors to become forgotten or worse—a concern that she expressed in her address to AFP Global members.

“What’s forgotten is often repeated,” she says. “Denialism is alive and well in Canada, and probably in the U.S. There are people alive today who have brothers and sisters and aunts and uncles who didn’t come home [from residential schools]. That’s a fact. And we’re not liars. We don’t make this [stuff] up. We don’t talk about it because we have nothing better to do—who in their right mind would talk about this stuff if they didn’t have to? It’s part of our history. It’s part of who we are. And it’s hurtful.”

The special interlocutor associated with the TRC once expressed the view that “denialism is the last step in genocide, and I really believe that,” Webstad adds. “So that’s one thing I asked [AFP members] to do, is to address denialism when they come across it. … Because there are those out there that say, ‘Everything from this doesn’t exist,’ that it wasn’t as bad as we say, or that there’s no children in the ground. There’s no graves. And we, as Indigenous people, have enough to deal with, without having to deal with deniers.”

Many Canadians of a certain age don’t know the story of how residential schools worked because they were never taught it in school, Webstad says. “In order for the world to be different, people need to know our truths, and truth comes before reconciliation,” she says. “That’s usually my approach.”

Webstad believes she raised awareness during her appearance at AFP ICON. “There’s not many Indigenous people who are a part of AFP or even know about it, for that matter,” she says. “So, in order for those who are there to be comfortable in the presence of an Indigenous person, they need to know the history. That’s the first step in having Indigenous people be part of that organization.”

Webstad hadn’t known much about AFP until recently but calls it “an amazing organization” and has been encouraging colleagues to consider joining. “The first thing is relationship-building,” she says. “In our Indigenous way, that’s what we do first, is build a relationship, share a meal together, get to know one another. And then other things are possible after that.”

During a photo session with about 15 AFP members after her appearance, only one or two of whom were Indigenous, Webstad says she heard “pretty profound” reactions to her story. And that reinforced the power of the type of storytelling that AFP members do all the time.

“That’s basically what I do, is storytelling, teaching history through story,” she says. “That’s the Indigenous way. If you ask an Indigenous person a question, the answer will probably be in story format. So that’s how Orange Shirt Day was founded, by telling my story of having my shirt taken away, and the history of my life, and how that connects to the history of Canada, with the Indian Act, with the residential schools, with the fallout of all of those laws, and stuff that the government forced upon us. And my grassroots-level experiences in relation to those policies and laws over the generations.”