Ethics: Mapping the Minefield

Insights into controversial donations and policies can help form fundraisers’ actions

Recent years have seen several high-profile cases of tainted donations in the philanthropic landscape. Consider, for instance, notorious cases like the Sackler family’s donations to the Metropolitan Museum of Art amidst the opioid crisis, and Jeffrey Epstein’s donations and interactions with MIT and Harvard. Scrutiny is also rising over contributions and relationships with regimes commonly considered by Western countries to be authoritarian or otherwise problematic, such as Saudi Arabia, Russia, and China.

These instances have sparked intense debates about the ethics of accepting funds from morally compromised sources and seemingly notable reputational damage to exposed institutions. Their publicity may also cause us to overestimate the frequency of controversial donations. So, how often do fundraising professionals actually encounter controversial donors? And do they have policies for responding to them?

Charting Controversial Donors

A pioneering study conducted by the AFP Foundation for Philanthropy and the Max Planck Institute for Human Development provides unprecedented insights into the frequency of controversial donors and the policies that govern their donations.

In this context, we define a “controversial donor” as a donor or prospect who holds a criminal conviction or exhibits behavior or attitude to the extent that it would prompt reluctance to accept their gift.

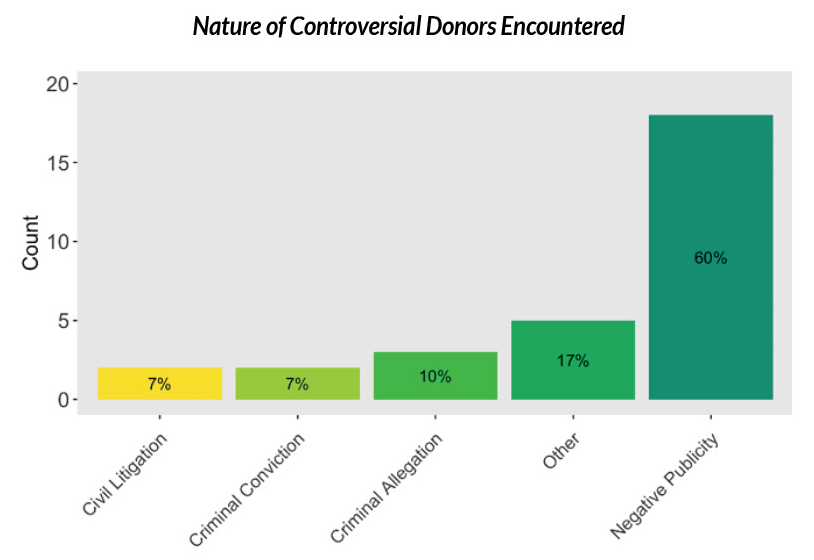

Our study, involving 52 AFP members, found that half had encountered a controversial donor in their professional experience. The nature of controversial donors varied, with the majority of donors (60%) having generated negative publicity regarding their behavior or attitude. Only a minority of controversial donors were subject to any criminal or civil legal allegations or convictions. “Other” included references to a donor specifying discriminatory use of funds or having values not aligned with the charity (e.g., religious fundamentalism, having an unsavory source of wealth).

Our study, involving 52 AFP members, found that half had encountered a controversial donor in their professional experience. The nature of controversial donors varied, with the majority of donors (60%) having generated negative publicity regarding their behavior or attitude. Only a minority of controversial donors were subject to any criminal or civil legal allegations or convictions. “Other” included references to a donor specifying discriminatory use of funds or having values not aligned with the charity (e.g., religious fundamentalism, having an unsavory source of wealth).

We also examined the frequency of controversial donors in current and past prospect pools. For AFP members having reported exposure to controversial donors, they most commonly reported that 1% of existing or potential donors generated a level of controversy that prompted reluctance to continue accepting their funds. A minority reported up to 5% of existing or potential donors were controversial.

Although a relatively rare phenomenon, there is a common belief that the frequency of controversial donors is rising. According to our survey, 54% of AFP members surveyed perceive an increase in the frequency of such donors over the past five years. Interestingly, this perception is even more prevalent among the general public. In a separate survey of 600 U.S. residents, 66% shared the belief that the number of controversial donors has been growing.

While there appears to be a low frequency of controversial donors, only one is needed to inflict significant damage. As one fundraising professional aptly put it, a controversial donor is like a nuclear weapon: Just one could cause enormous damage to an institution’s reputation. Further, the perceived increase in the frequency of controversial donors motivates the need for institutional awareness of the challenge and preparedness to ensure effective organizational responses.

Policies Regarding Controversial Donations

Given this, it was somewhat surprising to learn that only 35% of AFP members surveyed reported their institutions having specific policies for handling controversial donations. Encouragingly, just completing the survey spurred one participant to approach their board to discuss the matter. We learned from comments made in the survey that many institutions take a “case-by-case” approach to controversial donations—an approach that may be efficient given their seemingly low frequency. There is also the possibility that institutions may not wish to have their hands tied if a generous-yet-controversial donor emerges—and therefore avoid developing such policies.

We also discovered that among those institutions that did have controversial donor policies, just over 20% of such policies explicitly forbid gifts from criminal donors. In a separate-though-related survey of the public, we found only a weak preference for policies that categorically reject criminal donations, with only 33% of the 600 respondents endorsing this approach. This is despite our previous research revealing that both the public and AFP members generally are intolerant of donations from criminals (as discussed in our earlier article, “Using Science to Navigate Tainted Donations,” in the October 2021 issue of Advancing Philanthropy). This discernible contrast between the preference for refusing donations from criminal donors and the notable scarcity of policies explicitly prohibiting such donations may hint at an underlying desire for adaptability within organizations. It may be reflective of an inclination to weigh each situation individually and maintain a case-by-case approach, rather than enforce a rigid policy that might restrict viable fundraising opportunities.

We also discovered that among those institutions that did have controversial donor policies, just over 20% of such policies explicitly forbid gifts from criminal donors. In a separate-though-related survey of the public, we found only a weak preference for policies that categorically reject criminal donations, with only 33% of the 600 respondents endorsing this approach. This is despite our previous research revealing that both the public and AFP members generally are intolerant of donations from criminals (as discussed in our earlier article, “Using Science to Navigate Tainted Donations,” in the October 2021 issue of Advancing Philanthropy). This discernible contrast between the preference for refusing donations from criminal donors and the notable scarcity of policies explicitly prohibiting such donations may hint at an underlying desire for adaptability within organizations. It may be reflective of an inclination to weigh each situation individually and maintain a case-by-case approach, rather than enforce a rigid policy that might restrict viable fundraising opportunities.

We hope that the findings of our current research will prompt reflections on the need to either establish or refine controversial donor policies in members’ organizations. Further, we hope that—where policies are desired—the findings of our prior research on what shapes acceptability of controversial donations can help guide thinking on the development or refinement of controversial donor policies—and perhaps even inspire research among relevant stakeholders to ensure that policies are tailored to individual organizational values.

For institutions that do have policies or are seeking to create such policies in keeping with the spirit of the AFP Code of Ethics, it seems important to calibrate any such policy for its own values, mission, and stakeholders. By carefully handling controversial donors, the positive impact of philanthropy can be amplified while mitigating potential risks.