Not a Monolith: Honoring Asians and Pacific Islanders by Recognizing Disparate Racial Experiences

I’ve always been proud of my multiracial identity. From the Japanese soba noodles and mochi we’d eat every New Year, to the Dutch-Indonesian babi kecap (braised pork) my grandmother would regularly cook, I’ve always felt connected to, and celebrated, my mixed Asian and European background.

When I was young, my family would fly koinobori (carp-shaped windsocks) to recognize the traditional Japanese Boys’ Day. And my grandparents’ story of displacement, migration, and sacrifice—ultimately arriving in Salem, Oregon, halfway across the world from their home in Sulawesi, Indonesia—has always been central to my motivation to do good in the world.

Growing up in Hawaiʻi, the most ethnically and racially diverse state, added an additional layer of cultural richness to my upbringing. But even as a young kid, there’s one thing I knew for certain: I live in Hawaiʻi, but I am not Hawaiian.

I don’t even remember being taught this. Deeply woven into the fabric of society here is the understanding that the term is exclusively reserved for the Kānaka Maoli, the descendants of the islands’ original inhabitants. Instead, people like me are “Hawaiʻi residents”—settlers on a land forcefully dispossessed.

Being cognizant of this distinction my whole life—that I am Asian, but not Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander—has given me the perspective to see that true solidarity and progress can only come from truly understanding the vastly different experiences of these groups.

Too often, our discourse puts Asians and Pacific Islanders together in a single category: “AAPI.” Because Pacific Islanders are not the same as Asians, amalgamating these identities only obscures the beauty of each individual culture—and the specific challenges that each group faces. By “disaggregating” data, or separating out statistics for Asians versus Pacific Islanders, we can get a much clearer picture—and begin working toward the solutions we urgently need.

For example, it’s important to understand that Asians and Pacific Islanders face vastly different socioeconomic conditions. Among Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, 18% live in poverty—higher than the national average of 14%—with a median household income of about $57,000. Asians, on the other hand, have a lower poverty rate than the national average, 12%, with a median household income of $81,000. (However, Asians are not a monolith either. Income and poverty levels vary dramatically among Asian subgroups.)

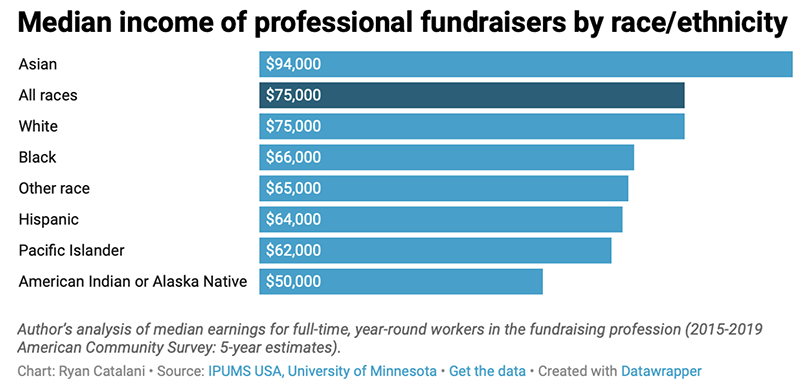

This disparity appears to be reflected even among professional fundraisers. Although disaggregated data for our industry is scarce, figures from the American Community Survey indicate that Asian fundraisers have a median income of $94,000—higher than even the median for white fundraisers. Pacific Islander fundraisers have a median income of just $62,000, which is higher only than American Indians or Alaska Natives, whose median income is $50,000.

This economic data was collected before COVID-19, but all indications suggest that the pandemic will only widen these disparities. A March 2021 analysis by American Public Media found that across the US, Pacific Islanders have a COVID-19 death rate twice as high as Asians. In Hawaiʻi, Pacific Islanders had a mortality rate eight times higher than Asians, according to the state Department of Health. Yet as of May 2021, just 22% of the state’s Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders have been vaccinated, compared to 47% of Asians.

You’ve probably heard of #StopAsianHate, but hatred toward Pacific Islanders is real too. In Hawaiʻi, Micronesians—people from several island nations in the western Pacific Ocean—face particularly intense hostility, with outcries recently renewed after police killed a Chuukese teenager. A 2019 survey from the University of Hawaiʻi found that 1 in 4 Micronesians in the state experienced bias because they were Micronesian.

Even though today, Asians and Pacific Islanders face different forms of oppression and animosity, these experiences share common roots in the systems of colonialism and violence that ensnare all people of color in the United States. As fundraisers, there’s much we can do, and are already doing, to dismantle these oppressive systems and replace them with liberation, joy, and justice. But it must start with a real understanding of the problems we intend to ameliorate.

Although this month celebrating Asians, Native Hawaiians, and Pacific Islanders is almost over, there’s still ample time to learn. These diverse cultures are filled with deep history and endless brilliance, with a multiplicity of stories, art, music, and other traditions, and they deserve to shine. As James Baldwin once said, “Hope is invented every day.” Together, we can create more hopeful days to come.

Ryan Catalani (he/him) has collaborated with marginalized communities across the Americas to galvanize solutions to some of the world's most pressing issues, including immigration, displacement, and homelessness. He currently serves as Director of Advancement at Hawaiʻi Children’s Action Network. Ryan is also a board member of the AFP Aloha Chapter, chairs its IDEA (Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access) Committee, and was a 2020 AFP Outstanding Young Professional awardee.

Ryan Catalani (he/him) has collaborated with marginalized communities across the Americas to galvanize solutions to some of the world's most pressing issues, including immigration, displacement, and homelessness. He currently serves as Director of Advancement at Hawaiʻi Children’s Action Network. Ryan is also a board member of the AFP Aloha Chapter, chairs its IDEA (Inclusion, Diversity, Equity, and Access) Committee, and was a 2020 AFP Outstanding Young Professional awardee.